Despite the government’s efforts to create sustainable marine and fisheries, it seems that Indonesia still has a long way to go. It is obligatory for sustainable fisheries development to be followed by optimal, healthy, and efficient utilization principles, which are not easy. Some of the challenges we face are illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing (IUUF).

For years, IUUF has been a major threat to the Indonesian marine and fisheries sector. According to the journal issued by Gadjah Mada University, the impact of IUUF practices has resulted in the disruption of sustainable fisheries management and caused economic losses for many developing countries and can also lead to: (1) decrease in catch which in turn leads to fish scarcity; (2) a decrease in the stock of fish resources, and (3) lost opportunity social and economic prosperity of fishers who operate legally. The omission of the practice of IUUF leads to the threat of sustainable fisheries management. FAO noted that the annual loss experienced by Indonesia is estimated at USD 3.125 million or Rp30 trillion.

One of the most common ways that fishers practice IUUF is by marking down their gross tonnage (GT) vessel size on official reports. In this practice, fishers would report measurements of their ship’s length, width, and depth that are lower, effectively avoiding bigger taxes. Because the process of applying for fishing licenses is quite lax and largely not strict, this practice lives on. Baked on the Regulation of the Minister of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries of the Republic of Indonesia Number 38/PERMEN-KP/2015 concerning Procedures for Collection of Non-Tax State Revenue at the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries originating from Fisheries Fees, taxes are paid depending on the size of each vessel. The Fishery Products Levy (PHP) that must be paid is 5% for small vessels (30–60 GT), 10% for medium vessels (>60–200 GT), and 25% for large vessels (>200 GT).

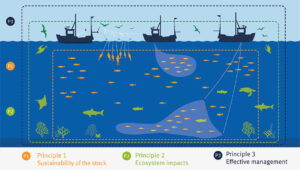

As has been widely discussed in the past week, within 100 days of the leadership of the Minister of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Wahyu Sakti Trenggono, as many as 67 fishing vessels were caught in violation of IUUF. Among them were 5 Malaysian-flagged vessels, 2 Vietnamese-flagged vessels that carried out illegal fishing, and 60 Indonesian-flagged vessels. All 67 operated without a clear permit and, of course, have a negative impact on fishery stocks. In addition, the illegal vessels did not provide clear reports on the number of catches and whether the amount is in accordance with the provisions of the maximum catch limit, and whether they used destructive fishing gear (API) such as trawling. Overall, the ships have potentially harmed the marine ecosystem and reduced state revenues. Destructive Fishing Watch (DFW) Indonesia encourages special operations against fishing vessels that are proven to have violated regulations by marking down ships, operating on expired permits, submitting false catch reports, and operating unofficial ports. DFW Indonesia National Coordinator, Moh. Abdi Suhufan said that there were still many recorded violations committed by ships in Indonesia’s fisheries that have not been caught by ministry officials. Not to mention the myriad of fishing vessels smaller than 30 GT operating without any permit at all.

A study conducted in 2018 related to the loss of fish resources (SDI) due to the practice of marking down ships showed that the existence of this illegal practice has led to depletion or reduction in fish resource assets in Indonesian waters, which can be an indicator of overfishing and eventually can threaten the sustainable management of capture fisheries. The sizable economic loss as a result of this practice is also shown by the magnitude of the value of resource depletion in 2015 which reached Rp9.83 trillion and is predicted to increase to Rp14.55 trillion in 2020.

The urgency to reach sustainability in the fisheries and marine sector is more obvious than ever. All the negative impacts of weak supervision and prosecution of illegal practices, of course, cannot be judged only in terms of economic losses, but also from environmental aspects in the long term. Special operations on fishing vessels that are “leaning” on the entire coast of Indonesia or are sailing, must be carried out by the Government. This of course also supports the commitment of the Government of Indonesia, especially as stated at the High Level Panel on Sustainable Ocean Economy last year, which must be made harder and smarter. It’s time to pair our statements of hope and promises with real action.